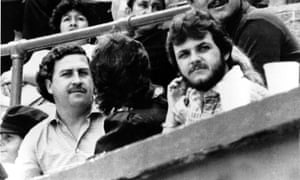

Pablo Escobar, left, watches a football game in Medellin, Colombia in 1983. Escobar and other cartel bosses were heavily involved in the game Photograph: AP

He’s a forward-thinking coach in MLS, but as a player, Oscar Pareja had a front-row seat in the days when Colombian soccer was dominated by drug cartels

Oscar Pareja was a bright-eyed 21-year-old when the tragic news filtered through. It was the evening of 15 November 1989, and he was heading home after Deportivo Independiente Medellín’s league clash with America de Cali. A man who he had shared a field with earlier had been murdered in cold blood on the streets of Pareja’s home town.

Pareja, part of the Medellín midfield engine room that day, was startled. The victim, Alvaro Ortega, had refereed the encounter, one which Medellín needed to win.

The murder was no random act. The Colombia of the 1980s and 90s was dominated by drug cartels. There were few areas their tentacles failed to reach. They built houses for the poor. They were involved in politics, gambling and bribery. And football. But when things didn’t go their way, bloodlust often ensued.

The king of them all was notorious cocaine lord Pablo Escobar, whose empire at one point dominated 80% of the global cocaine market while simultaneously ripping apart Colombian society. But there was a turf war. His Medellín cartel had a chief rival in the Cali cartel to the south, headed up by prominent foes Gilberto and Miguel Rodriguez Orejuela. And the rival cartel bosses shared more than a lust for control of the drugs trade. They were soccer fanatics with stakes in at least three top clubs between them.

For referee Ortega, that proved fatal. Medellín was said to be owned or linked to Escobar, who was more commonly associated with city rival Atletico Nacional. America belonged to the Cali brothers, a pair often euphemistically referred to as “the gentlemen” after their preference for bribery over violence.

Reports vary, but it seems Escobar ordered Ortega’s death when decisions had gone against Medellin in a previous game against America.

It’s an all too raw memory for Pareja. “We needed to win,” he tells the Guardian. “I thought the referees had had a bad performance. When I was going back home after the game we heard that one of the referees was killed. I remember we were numb.”

It was a fraught time. Yet Pareja remembers he and his team-mates were unable to fully grasp the gravity of the events going on around them.

“That problem was there. It was part of our society. I can tell you now after time has gone by, we can see now clear how those days were. I thought then they were involved there somehow. We could feel it. We were numb. We didn’t know much better. We knew that we needed to play for the team. We knew we had to defend the colors of the club. And we needed to fight for our fans.

“But we knew there was a lot going on with the owners of the club, that they were very shady and [there were] things that we didn’t know. When you are a soccer player you don’t know much about those things.”

It’s a far cry from the tranquillity of life now. Pareja is a prized asset of the FC Dallas homegrown-driven juggernaut. As head coach, he is known for developing young talent that may otherwise go astray – an ingredient that perhaps draws from his own blighted youth in the pressure cooker of Colombia in the 1980s and 90s. And at Dallas, he has placed a small corner of Colombia amid his ranks, components of the burgeoning talent pot that makes up the current generation of the country’s footballers.

MLS all-star and FC Dallas left winger Fabian Castillo is one. Fellow winger Michael Barrios, an even more diminutive presence on the right, has been showing promise recently having been acquired by Pareja from the Colombian second division.

Pareja’s own generation put Colombian football on the map. After making their first World Cup appearance in 28 years at Italia 90, they returned again for the 1994 tournament in the United States as one of the favorites. The upsurge in the Colombian domestic game may have owed much to the investment of tainted money, but the talent of emerging players like Faustino Asprilla and peaking veterans like Carlos Valderrama was genuine. Pareja was among the Colombian game’s top players when the national team made a fourth-placed finish at the 1991 Copa America, but not for the World Cup three years later. He watched on in horror, though, as his country and friends crashed out in the group stages under the weight of unwanted pressure from home.

“The national team, when they came to the United States World Cup, they received a lot of pressure from many people who didn’t belong to the game,” Pareja recalls. “And it put the players in a place where they were not in the right state of mind. Players being threatened by people who were betting for games. Players who were feeling the pressuring of problems that was there, and empowered by people who were crazy. That was very difficult to overcome. And that magical generation just surrendered under the pressure of the shady people who don’t do right.”

It was a bewildering time. And Pareja had a front row seat. Literally.

In the years to come, before he left his homeland for MLS in 1998, the now 46-year-old would live through many more incidents of intrigue and skulduggery, some tragic like the death of Ortega. There were attempts on the lives of presidential contenders, and Luis Carlos Galan was assassinated the same year as Ortega. There were bombings. But others simply entered the realms of the absurd.

Perhaps the most bizarre: taking his own personal orders from Escobar. Along with a group of Medellin teammates, Pareja was summoned to the infamous drug czar’s self-built, one-man prison in the foothills overlooking the Andean city. Pareja is a stoic figure, uncompromising as a football man on the FC Dallas touchline. But as he recounts those strange days, Pareja’s gaze narrows briefly, fixes on his midriff, the merest hint of nervousness as he remembers that time in his life. It is not one he likes to recall.

“I was demanded, we were demanded – not in a bad way, you know,” he says. “As I said, those people were looked at in this time as Robin Hoods. So, back in that time when you receive a call and said you needed to go and play with Robin Hood and his people, you see it as an appearance that is going to bring joy to someone in the jail.”

Robin Hood seems a peculiar choice of moniker. But Escobar and other cartel leaders were known to build houses for the poor and other community amenities, however twisted their motives many have been.

But joy? “I got to tell you something, Colombia in those days with soccer and all what was happening, there was a lot of joy,” says Pareja. “And the game just embraced everybody in a certain way. So when we were playing we were just having fun with people who, many of them, you see growing in your community. Now the people see, it gets bigger and bigger, but back in that time we were people who just loved the game and shared it.

Now I can see back and see different. But back there when we were doing it, we were just, with policemen, with the guy who sells you the milk, with the guy who is a professional like you, with Robin Hood, with everybody. We were invited to go everywhere. With the kids that were in the hospital, with the kids that were less fortunate, with people who were in the jail, we made a lot of appearances.”

In Escobar’s prison, named La Catedral, Pareja and his team-mates played the drug lord and his henchmen, taking care to ensure the score remained close and avoiding any rash tackles. In person, Pareja is immensely pleasant, and Escobar, too, was enamored. He called Pareja by a popular old nickname, El Guapo, or “the handsome one”. But Escobar also noticed Pareja’s habit of arguing decisions. Escobar apparently informed Pareja that his protestations were futile, the decisions preordained by the drug lord.

It was all a long time ago. Pareja left his homeland as it was still struggling to cope with the aftermath of the big cartels. A civil war, too, continued to rage. Today, things are calmer, a pleasing aspect for a man who has previously spoken of a desire to one day return home to the family ranch.

The nation’s game is also riding a wave of optimism unknown since the generation to which Pareja belonged. Colombia’s 1994 World Cup squad was the pinnacle of a journey which began at the 1990 tournament in Italy. It was festooned with talent. Names such as Valderama and Asprilla, as well as Antony de Avila, Freddy Rincon, Gabriel Gomez. And the one seared into Colombia’s – and football’s – conscience: Andres Escobar. Andres was another man gunned down on a Medellin street, his untimely demise occurring after the 1994 World Cup, and after Andres, a teammate of Pareja at the 1991 Copa America, had scored a fateful own goal in Colombia’s second group match against the United States. By this time Pablo Escobar had been killed by the authorities, but the lawlessness of the country prevailed.

Perhaps he has to be, but Pareja is a passionate follower and proponent of Colombian soccer and the product it churns out. These days, that output is not inconsiderable. The current generation of Colombians, probably the most stylish at last year’s World Cup in Brazil, might be the natural successor to the one which featured Pareja the player. That squad may have been Colombia’s best ever at the time, a golden generation robbed of a true shot at glory.

The question might be, can this generation, with all of its bubbling talent, social and political advantages do what their predecessors of the early-to-mid 1990s couldn’t? A win in Russia in 2018 seems somewhat hazy right now, particularly after Colombia’s lackluster excursion at the recent Copa America in Chile. But for the core of this promising Colombian collective, largely born in the aftermath of the era darkened by the major cartels, a fairytale triumph would rank as a fitting tribute for the generation who had their best chances effectively ripped from their grasp.

“Are we going to be able to win a World Cup? I think we will have a chance. With this generation we probably do. We have a lot of talent there. But it is not easy to win a World Cup,” says Pareja. “But I think we are on a great path. I think our country financially, economically, politically, my society is striding toward a good place. Our ingredients are there. I think we have a better country, we have better people around.”